Nuclear submarines and 'Dead Hand': Trump–Medvedev clash revives Cold War fears

A Cold War doomsday switch is back in the headlines

Russia’s “Dead Hand” was built to answer the worst day imaginable: a nuclear strike that wipes out national leadership. This week, that automated Cold War relic resurfaced in public threats after a sharp online exchange between Donald Trump and Dmitry Medvedev, a senior Russian official and former president.

On August 1, Medvedev posted that Russia’s nuclear forces were ready to answer hostile moves, name-checking the Perimeter system—better known in the West as Dead Hand. Trump, blasting the message as dangerously provocative, said he ordered two US nuclear submarines shifted to “strategic locations.”

Here’s the rub: Trump is not in office. The US military chain of command runs through the sitting president and the defense secretary. As of publication, the Pentagon had not confirmed any change in submarine deployments tied to Trump’s remarks. The Navy almost never comments on ballistic-missile submarine (SSBN) patrols, so public confirmation was always unlikely. Still, Medvedev’s decision to invoke Dead Hand—a system designed to launch a retaliatory strike even if Russia’s command is destroyed—pushed the rhetoric into darker territory.

The broader backdrop is the grinding war in Ukraine and a thin layer of arms control. The last US-Russia treaty capping deployed strategic weapons, New START, is barely functioning: inspections are suspended, data exchanges are limited, and trust is scarce. When arms-control guardrails fade, small signals—tweets, patrols, flight paths—get read as big moves.

US and European officials have warned for months about the risk of miscalculation at sea. The North Atlantic, the GIUK gap (Greenland–Iceland–UK), and the Barents and Norwegian seas are again busy. Russia tries to protect “bastions” near home waters for its SSBNs. The US and allies run surveillance and anti-submarine patrols along approaches to those bastions. One misread sonar contact in bad weather can turn into a crisis call between capitals.

- What we know: Medvedev publicly referenced Dead Hand; Trump publicly claimed to reposition SSBNs; navies on both sides are active in the Atlantic and Arctic.

- What we don’t know: Whether any US SSBNs actually shifted because of Trump’s statement; whether Russia changed its nuclear alert posture; what the day-to-day orders to submarine crews look like right now.

How the undersea balance stacks up—and why Dead Hand talk matters

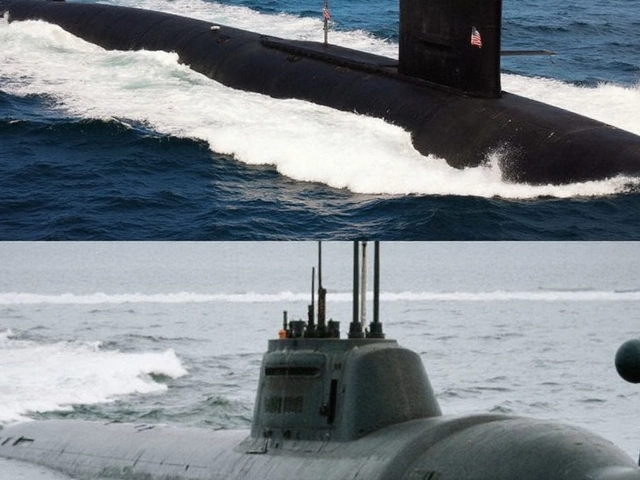

SSBNs are the quiet leg of a nuclear triad. They hide, wait, and deter. The US operates 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. After modifications under treaty limits, each carries up to 20 Trident II D5 missiles, with intercontinental range and highly accurate guidance. The Navy is building the Columbia class to replace the aging Ohios, aiming for even lower acoustic signatures and upgraded command-and-control.

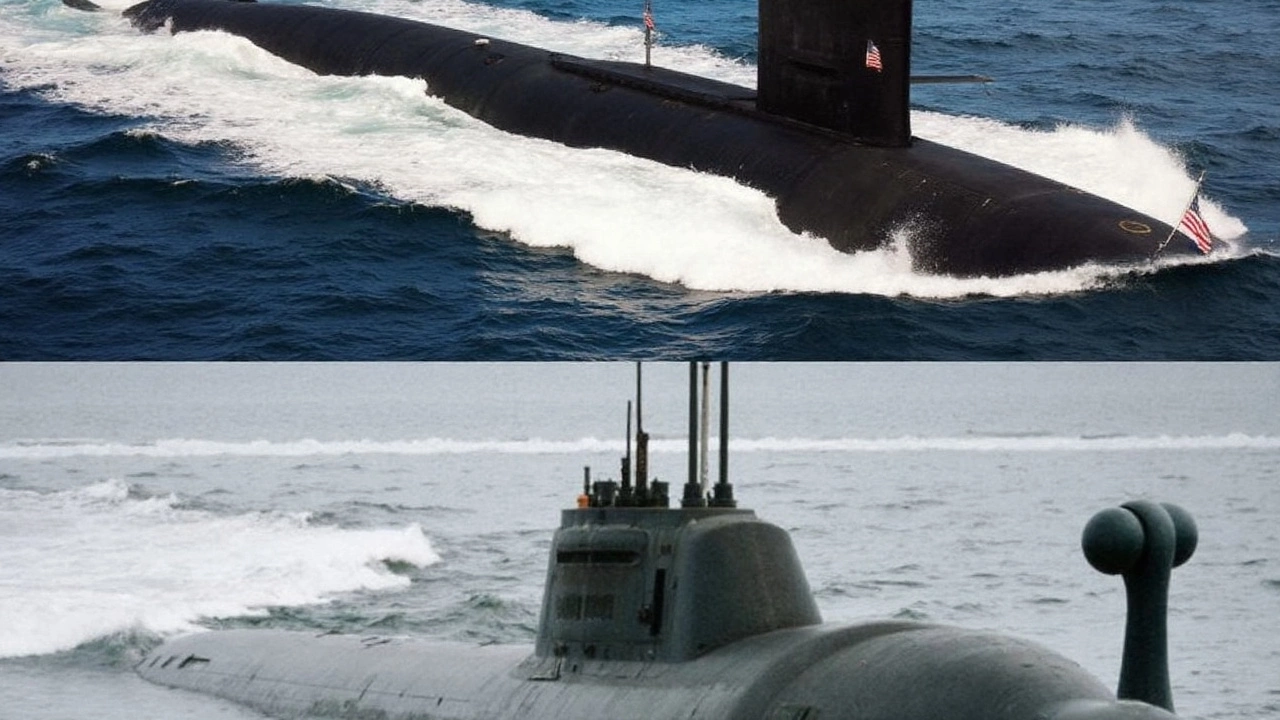

Russia’s newer Borei-class boats—Borei and Borei-A variants—are the core of its sea-based deterrent. Seven are commonly assessed as operational, with more hulls fitting out. Each carries up to 16 Bulava missiles. The Borei line is a big step up from older Delta-class subs, especially in quieting and automation. Russian yards have worked to cut hull noise and vibration, the currency of survival in a cat-and-mouse undersea game.

On paper, US boats still hold an edge in noise reduction, at-sea reliability, and missile accuracy. The US also benefits from a mature support web: satellite communications, ocean surveillance, and a large attack-submarine fleet trained to cover SSBN patrol areas. Russia has invested heavily to narrow gaps, including in sensors, seabed infrastructure, and advanced missiles like Zircon for other platforms. But its industrial base and maintenance cycles remain uneven, which can translate into fewer days at sea for some hulls.

Then there’s Dead Hand. Known as Perimeter, it’s not a single button. It’s a network built to sense extremes—seismic shocks, radiation, loss of communications—and, if human command is destroyed, route a launch order through a special “command” missile that relays instructions to other missiles. Russian officials mention it rarely. When they do, they’re signaling resolve and survivability under the worst conditions. Medvedev bringing it up was meant to send exactly that message: even a decapitation strike would not stop a retaliatory blow.

Deterrence theory leans on predictability. Both sides try to convince the other that first use would be suicidal. But political signaling by social media short-circuits the careful choreography. A single post can leap past backchannels and land in military inboxes within minutes. Officers who plan routes, set sonar search patterns, and draft rules of engagement don’t parse online sarcasm; they work from orders and alerts.

Analysts who track nuclear forces point to a few practical realities today:

- US SSBNs almost always keep a portion of the fleet at sea, on continuous patrols. Specific locations are classified, but patrol areas typically sit far from shore-based threats.

- Russia leans on “bastion” doctrine—keeping its SSBNs closer to protected home waters in the Barents and Okhotsk seas, under layers of air defense, surface ships, and attack subs.

- Both sides train to find the other’s boats in wartime. In peacetime, they mostly avoid close approaches to reduce collision risk, though history shows that line has been crossed before.

Arms-control norms used to add friction to escalation. Hotline calls and treaty notifications helped both sides read each other’s moves. With those tools weakened, patrols and exercises do more signaling work. A sudden exercise in the North Atlantic, a spike in anti-submarine flights out of Iceland, or a surge in attack-submarine departures from US East Coast bases becomes its own message.

So what would de-escalation look like? Quiet steps, not grandstanding. Backchannel reassurances that neither side is changing nuclear alert levels. Routine rather than surprise patrol patterns. Military-to-military contacts that clarify where ships and aircraft will operate. Even modest confidence-building measures—like advance notice of missile tests—help lower the temperature.

Meanwhile, the hardware race grinds on. The US Columbia class aims for a 12-boat fleet, fewer hulls than Ohio but with longer service lives and improved stealth. Trident II missiles are getting life-extension upgrades to fly through the 2040s. Russia continues to add Borei-A hulls and refine Bulava. The risk isn’t just the tech; it’s the narrow margin for error when politics heats up faster than navies can safely adapt at sea.

One final point about credibility: The US Navy won’t confirm where its SSBNs are, and Russian forces won’t advertise when a Borei slips out of Gadzhiyevo or Vilyuchinsk. That silence is by design. Submarines deter best when they’re unseen and unlocated. Which is why rhetorical spikes—invoking Dead Hand, claiming sudden submarine moves—can unsettle without changing a single patrol track. The danger lies in how those words get interpreted by watch officers staring at a sonar waterfall at 3 a.m.

Watch the Atlantic and Arctic, and watch the language. The boats will keep doing their runs. The question is whether leaders keep their signaling inside the lanes that have, so far, kept nuclear rivals from stumbling into a crisis they can’t control.